A Black Girl’s Field Guide to the Canadian Wilderness

Jenel Jackson

[fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [0000] version 1 1/2022

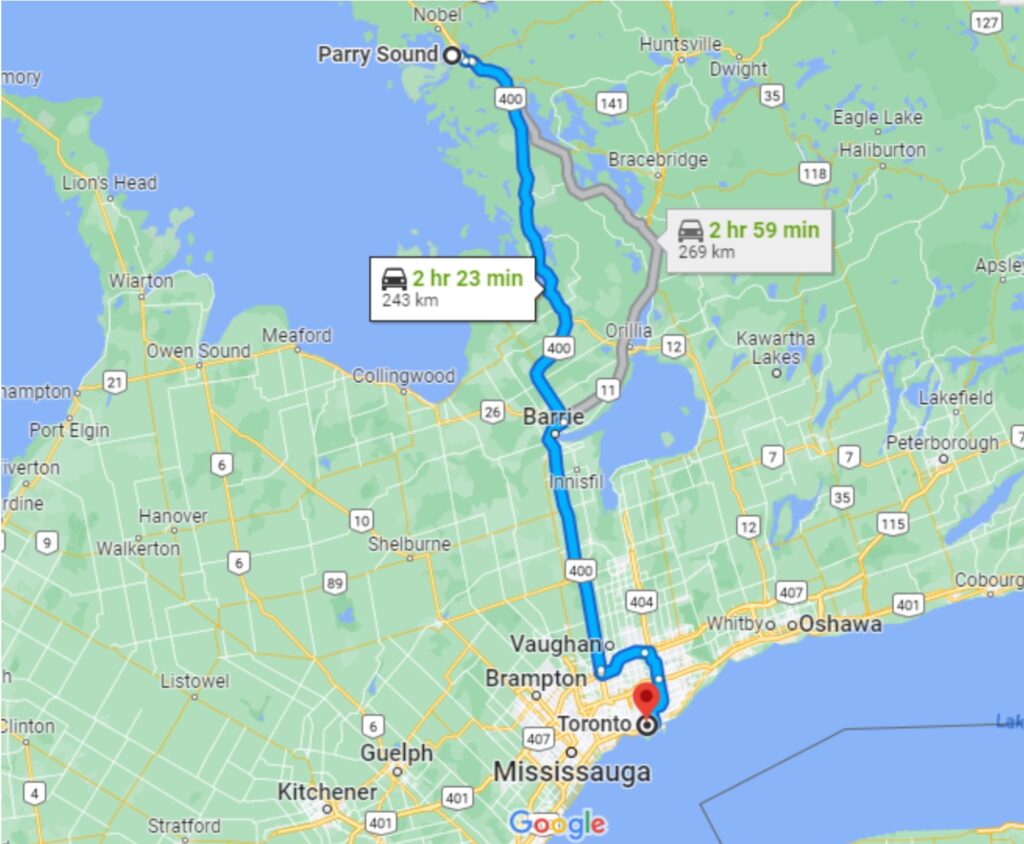

Figure 1. Map of Toronto to Parry Sound. From Google Maps, 2023, https://maps.app.goo.gl/f2Asx54fPfmTNHNf7.

General Information: Young Black girls seldom make good campers. The first time I went camping, I was 8 years old. I’d never been away from home before, let alone in the forests of Canada. My family has always lived in the city since my mother’s arrival, and before stepping into the campsite, the most wilderness I’d experienced had been a park. My mother braided my hair in neat cornrows to ensure that when I submerged into the water, my hair wouldn’t shrink, leaving a mess for me and the counsellors to navigate. My mother cried as I got on the bus; I wondered if I should too, but I didn’t. All I could do was wave from my seat inside before realizing she couldn’t see me. There were so many trees I didn’t know where to look; wooden cabins were placed sparingly throughout the grounds, and rooms were assigned. It wasn’t like Toronto; there weren’t any cars, honking horns, or noises from the bright screens of televisions. The only noises were the various bugs and the counsellors clearing their throats while trying to get the attention of the crowd of young girls. I quickly felt I didn’t belong. I’d never seen many of the insects that tried to crawl up my legs and arms or sneak into my shoes and bed; I’d never eaten many of the meals they fed us. The activities were fun for the most part: drawing, canoeing, swimming, and making fires. But this didn’t account for the moments I felt left out, the way many BIPOC feel left out in outdoor activities, like when we all gathered in a circle to do each other’s hair, and no one knew what to do with mine. The other girls got clips and flowers, and I sat aside weaving flowers through another girl’s long blonde hair, wishing mine looked like hers. |

Species name:

Average size:

The relationship between Black people and the outdoors is a fragmented one, camping and other outdoor activities are generally seen as White areas. In his 2019 article “Being a Shark,” Phillip Dwight Morgan delves into these feelings of Black unbelonging in the wilderness, he writes: “Our knowledge, much like the clothing we are shown wearing, is unapologetically urban and, therefore, alien to this particular vision of nature. There’s a subtle but clear message here, the messaging of absence, working in tandem with these stereotypes to tell us that we are not only gangsters, but gangsters unwelcome in Canadian wilderness” (Morgan). Black people have been depicted as savage and primitive, as though we belong in jungles and zoos, and yet so many Black Canadians have a strained relationship with nature and the wilderness. The freedom and exploration that come with the northern forests have been depicted as merely “White people things” (Morgan). Most Black Canadians have two reactions to the idea of camping: laughter and making jokes at the idea of doing activities usually associated with White people; and fear— of the unknown and being a Black person in the woods.

Rarity:

Years of separation leave quite a gap to be filled. A 2021 study by Erin Eck from Yale University describes various possible reasons for this gap, quoting Anderson she states that: “Black hikers draw an important distinction between hiking as a White activity and the trail as a White space (Finney, 2014; Anderson, 2015) that must be navigated with caution by Black hikers. Anderson defines the White space as a ‘perceptual category,’ ‘a situation that reinforces a normative sensibility in settings in which black people are typically absent, not expected, or marginalized when present’” (qtd. in Eck 5). The idea of nature-based leisure activities as a White space has been prevalent for a long time. Especially since the “norm” of the typical hiker/outdoorsman is a White, fit, cisgendered, middle- to upper-class man, as they were the ones who had time and money for leisure. As Black people separated and created an identity outside of White people’s, much of this was rejected and left behind as a “White people thing” (Morgan). However, this alone doesn’t account for the large racial disparities surrounding “nature-based recreation” (Eck 4). Many Black people are interested, as seen in Dwight’s article, and numerous Instagram accounts focus on getting or supporting marginalized people who enjoy or want to experience the outdoors. It’s not only Black people who feel unwelcome or are rarely seen in these spaces; people with disabilities, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, plus-sized, people of different religions, or women are all part of those who feel unwelcome. When they try, they feel the need to justify their existence within these spaces. This disconnect becomes harder to bridge as we get older.

Habitat:

There are organizations dedicated to helping marginalized communities cross this bridge, and their difference from those unspecific about the communities they serve (supposedly everyone) is stark. Eck’s research illustrates that Instagram accounts that were focused on these communities concentrated on individual experiences. They posted more about how to get started and things newcomers needed to know (instead of assuming awareness), posted photos of people who “looked like them” to have clear representation, and discussed building a sense of community so no one felt alone or like an outlier. Those who didn’t have a specific audience projected a certain “colour-blindness” with nature. They focused their photos on landscapes rather than people, and (mostly) if people were featured, their photos were obscure, likely from a distance or covered in gear, making it impossible to distinguish their race. (However, most models were White, with an occasional Black person.) This is meant to project being one with nature as a human experience (Eck 18-20). But one form of representation doesn’t equal representation for all. Posting about Black experiences once a year/whenever it is trendy and not for the rest of the year does not make you inclusive. These institutions rarely (if ever) post about trail etiquette or experiences, portraying the idea that they expect this to be common knowledge, but as seen in Morgan’s article, that is not the case. “[S]tudents mobilized an entire wilderness vernacular that revolved around Thoreau, the Group of Seven, campfires, and portaging. As you can imagine, they were genuinely shocked to hear that I’d only been in a canoe once before during a grade six trip and that I had no knowledge of the Canadian landscape painter Lawren Harris.” This can be extremely discouraging for those who’ve always been distant from nature and can add to already prevalent feelings of unbelonging. Eck’s research found no evidence illustrating a lack of interest or cultural/value differences surrounding nature. It is not just people from the Black community who feel excluded, but those who have yet to see people who look like them as “adventurers, explorers, park rangers, or zoologists” (Morgan) in the media. Though many would like to say nature doesn’t see colour, the people in nature do. There is a predominant culture surrounding outdoor activity, one that people of colour aren’t a part of.

State:

During my time at camp, I made friends, learned songs I sing to this day, and made memories I’ll carry with me forever. I became friends with a spider my friends and I named George Washington; I won best camper (and wore that shirt for years until it no longer fit and the words faded); I roasted marshmallows; I went to Powwows (or the White version of them anyway). Morgan almost became a shark; he trained for a half-marathon; he nearly stepped on a snake (practically unfazed); and he biked across Canada. We are here, we are interested, and we interact with nature in our own ways. But there is a feeling of being an outsider in more ways than one, and many just need encouragement to get out there. A sense of community is crucial to the diversity of the Great White North.

Eck, Erin. Departing from the Norm: Diversity, Representation and Community-Building in Outdoor Recreation. ycej.yale.edu/sites/default/files/erin_eck_research_paper.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec. 2025.

Figure 1. Map of Toronto to Parry Sound. Google Maps, 2023. https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Parry+Sound,+ON/Toronto,+ON/@44.4957596,-80.796063,8z/data=!3m1!4b1!4m14!4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x4d2bba8b144d357f:0x5037b28c7232810!2m2!1d80.034783!2d45.3473925!1m5!1m1!1s0x89d4cb90d7c63ba5:0x323555502ab4c477!2m2!1d-79.3831843!2d43.653226!3e0.

Morgan, Phillip Dwight. “Being a Shark.” BESIDE, University of Regina Press, 2019, https://beside.media/en/blogs/news/being-a-shark?srsltid=AfmBOopPaO0Wfb6Gj6DXObnNTkPc2MZJEJ7U8JTEGulNRbt5DyRvhsf4.

JENEL JACKSON is a 4th year English major with minors in Digital Humanities and Book and Media Studies. She’s an aspiring librarian, who hopes to apply to graduate school next year. Jenel wrote this essay in her first year but was too nervous to publish, so this is a leap.